Seeing With the Heart: How Billy Howard’s Sacred Photography Humanizes Illness, Disability, and the Invisible

Billy Howard enjoyed visiting the dentist. Not for the teeth cleanings or the jolt of accomplishment when checking off another routine to-do, but rather to joke with his dentist, Neil. Through a series of shared laughs, a friendship formed. Then, one day, Neil disappeared without explanation.

Eventually, Billy learned that Neil had been diagnosed with AIDS and had left town preemptively, hoping to shield himself from the stigma and rejection he might face from his community. This loss shook Billy. “He just vanished,” he recalls. “I considered him my friend. We were hilarious together.”

While Billy understood the fear that had driven Neil away, what haunted him more was how easily that fear eclipsed the deeper truth of their shared humanity and the expectation of empathy. Of love.

If Neil believed people would have seen beyond his diagnosis — that they would have seen his whole, complex self — perhaps he wouldn’t have felt the need to disappear. That realization marked a profound shift in Billy’s life and creative purpose.

From then on, photography became more than an art form. To Billy, the act and outcome of photography became a means to help both subjects and viewers access the Sacred. He discovered the power to transcend what can be visualized in the physical world and communicate matters of the soul. He discovered the importance of affirming the dignity and completeness of lives so often overlooked or misunderstood, especially those shaped by illness or disability.

Traditional medical photography serves a clinical function in society, documenting symptoms, tracking disease progression, and aiding clinicians in diagnosing and treating patients. While these visuals are beneficial and necessary to the medical management process, the cost is often dehumanization.

Illness and disability become the only narrative visible in the frame.

Medical photography sterilizes. It erases the rich, complex lives of the individuals being photographed. More troubling, this mimics the trap people can fall into when meeting or interacting with those experiencing medical challenges. We see them without seeing them. And when our inner world, identity, and experiences don’t match how our community interprets us, stigma and othering are born. People are left feeling embarrassed, ashamed, and invisible. Unknowable.

Billy recognized this problem early in his career, especially during the height of the AIDS epidemic. He saw how people living with AIDS were often reduced to hollow symbols of illness through the photography of the time, which used a more medical lens, stripping humanity from its subjects.

“Those images made people look like they were from another planet. It was hard to identify with someone that far removed from their normal self,” Billy recalls. These depictions didn’t reflect Billy’s own experiences. When he sat and spoke with people living with AIDS, he was struck by their tenacity, humor, and love for life, not their proximity to death.

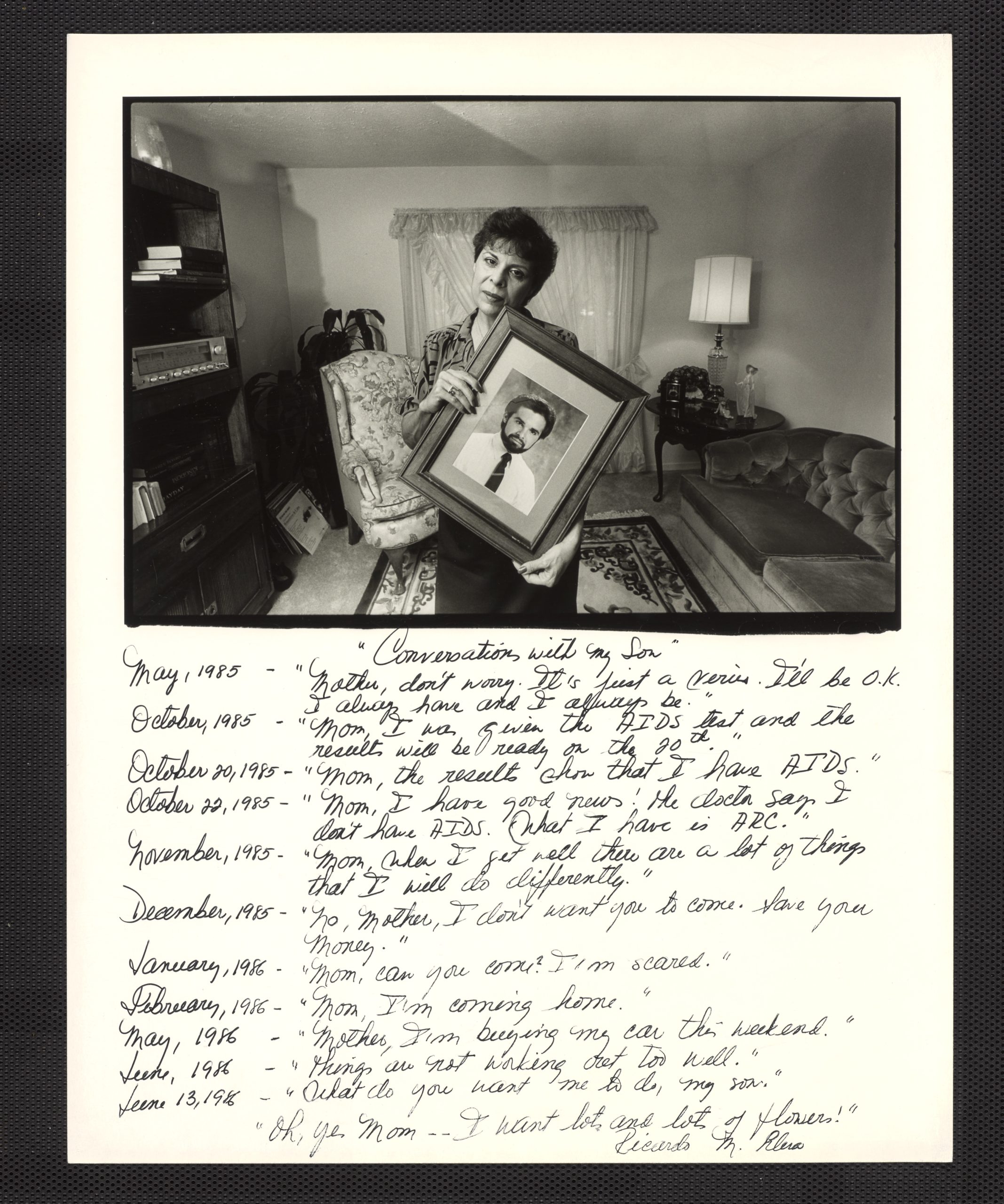

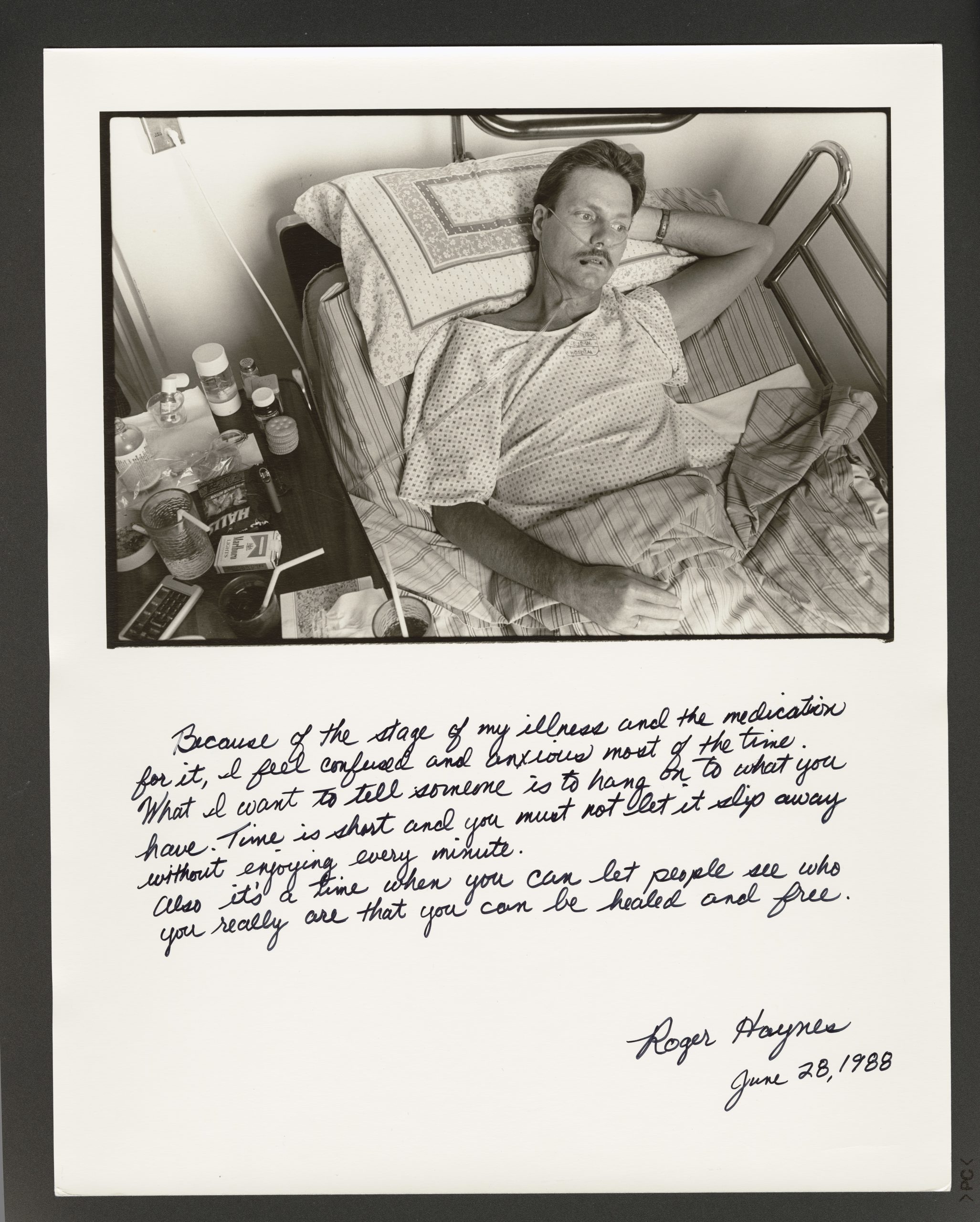

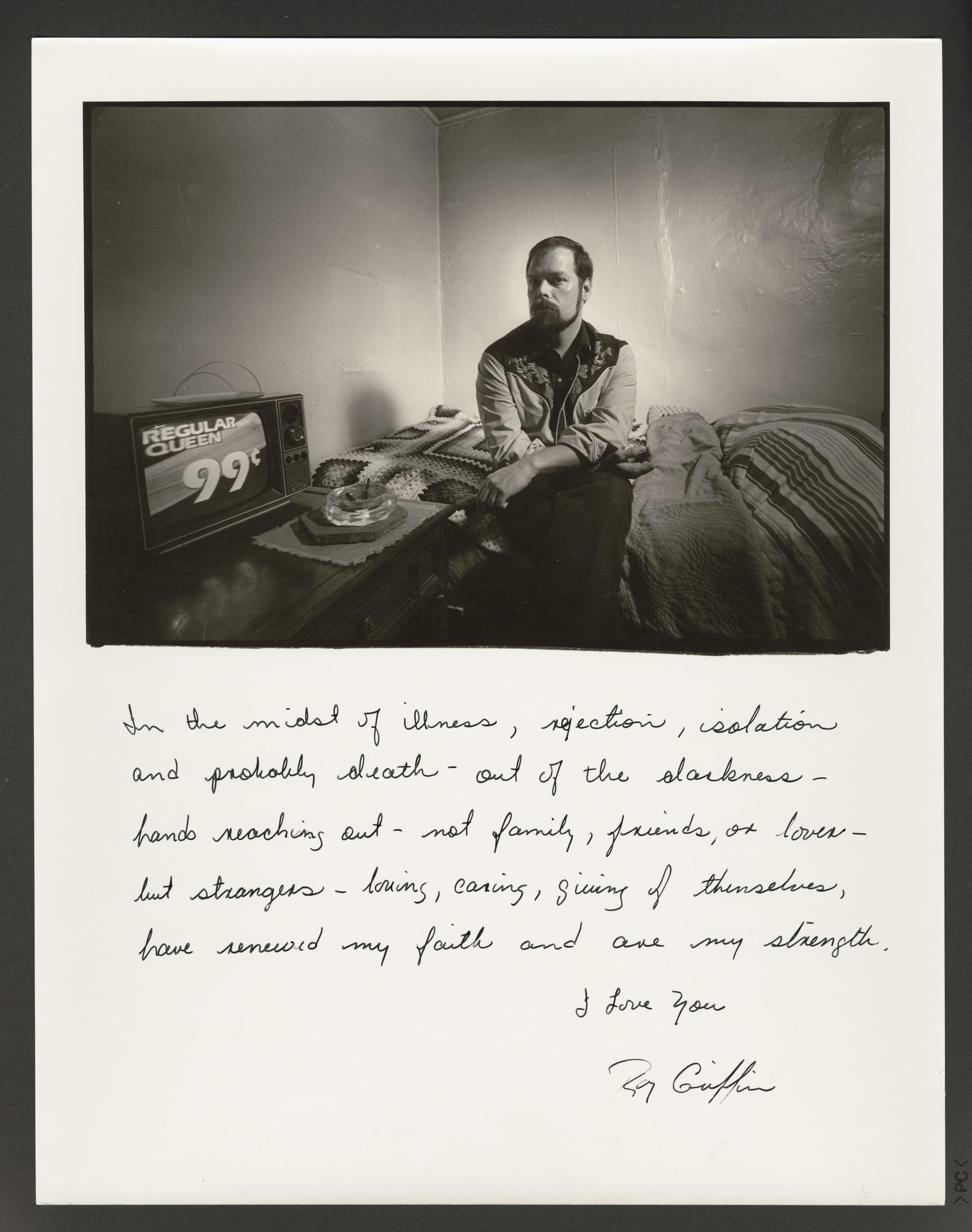

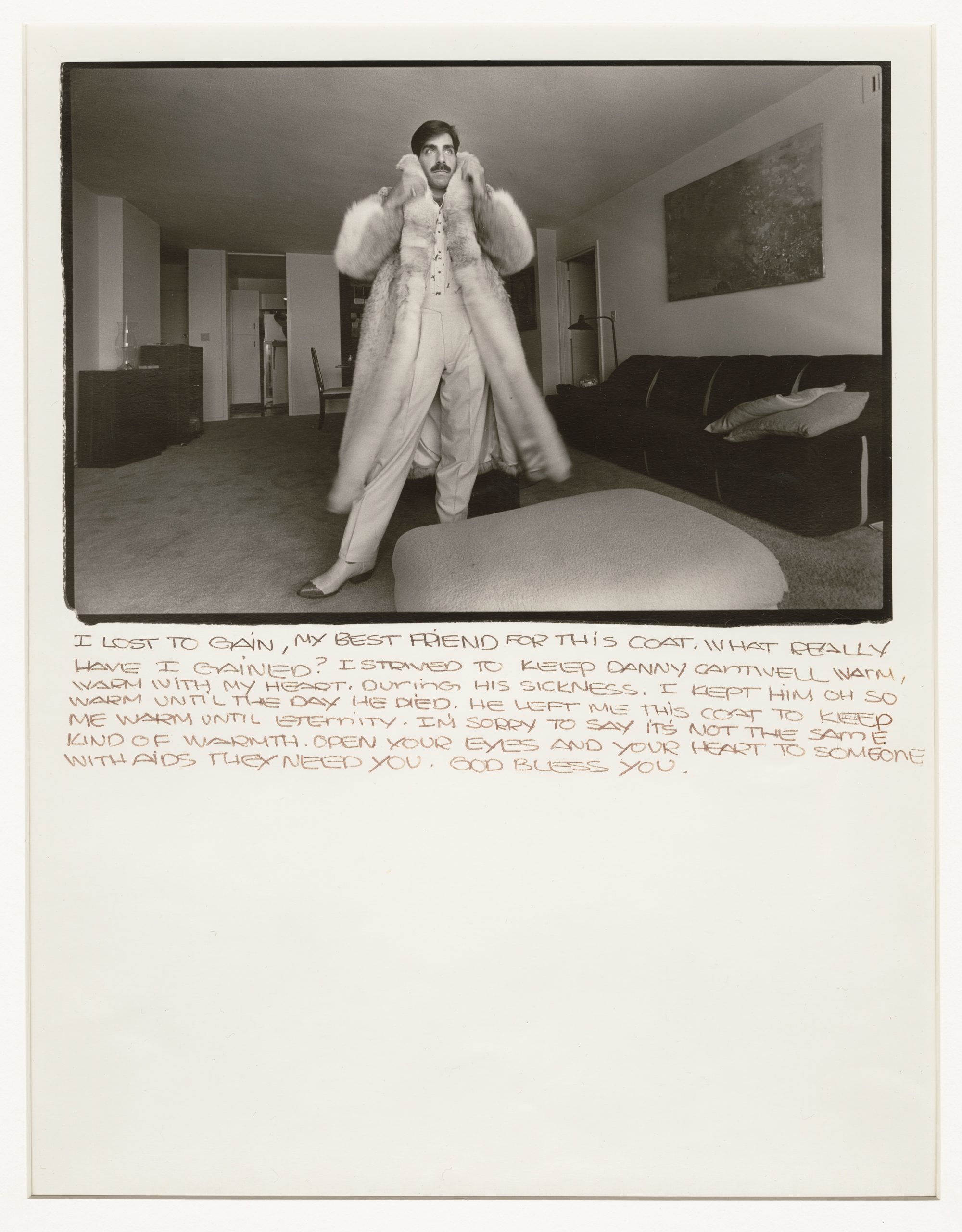

“People living with AIDS were seen as pariahs at that time. I wanted to give them a voice,” Billy shares. On multiple occasions, these individuals told Billy that sharing their stories felt like writing their own obituaries. The world around them spoke only of death, casting a shadow over their lives long before they ended.

Without ignoring suffering, Billy set out to change that one-dimensional narrative. “The people I was photographing weren’t dying. They were finding ways to live,” Billy says.

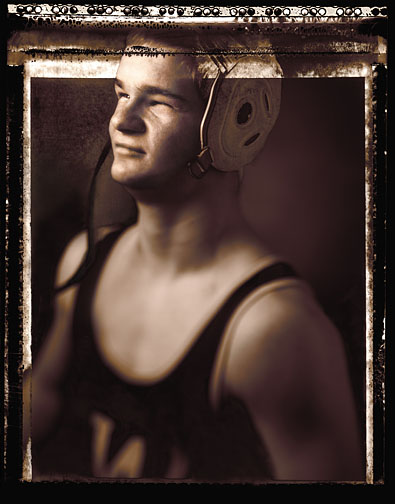

Their photographs and handwritten reflections became “Epitaphs for the Living: Words and Images in the Time of AIDS,” a book that honored their voices and affirmed their lives. One participant, David, reflected on the tension of his inner reality and what Billy’s photograph of him captured.

“In many ways, the photo doesn’t look like me. It doesn’t show the lesions growing on my face and body. It doesn’t show that I’m half-blind. It doesn’t show the fact that I’ve had 3 bouts of pneumocystis pneumonia in the past year and a half,” David writes. “[This photo] is how I want to be remembered: happy, attractive, self-satisfied, and content with life.”

Art, then, becomes a sacred act: a revelation, an illumination, a dialogue with the subject’s deeper truth. It has the ability to both reveal and preserve what is unseeable by the naked eye, becoming a way to tap into empathetic energy and relational love, promoting shared flourishing.

“These people are dealing with something that’s profound in their life, in their body, in their condition.” Billy shares. “It sharpens their focus on what it means to be a living person on this planet.” Beyond helping people see the sacred in one another, photography offers us a lens that reveals what the eyes alone often cannot see — a way of seeing that comes from the heart.

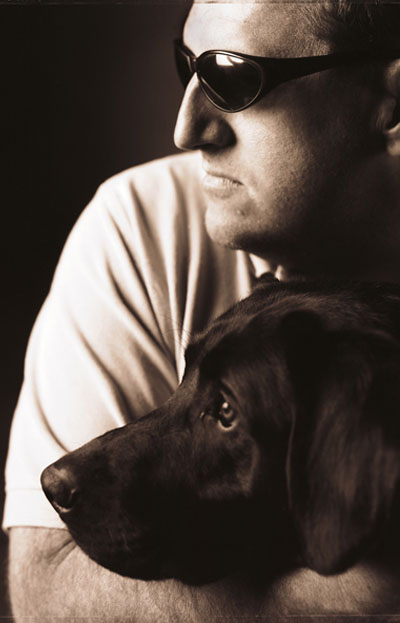

Guided by an ongoing commitment to use photography as a sacred act of seeing – and to identify shared sacredness in each other — Billy collaborated with his wife, artist Laurie Shock, to explore what it truly means to be blind. This project was especially meaningful to Laurie, who had experienced temporary blindness from detached retinas in both eyes.

That time reshaped her understanding of vision and perception. “People assume blindness means darkness,” Laurie says, “but there’s a spectrum. One can be blind and still have visual experiences.” The pair set out to help others understand the varied and often misunderstood ways people with vision loss experience the world.

To bring these perspectives to life, Billy and Laurie combined photography, illustration, and narrative storytelling to produce the Blind/Sight project for the Center for the Visually Impaired (CVI) in Atlanta, GA. Billy photographed each participant, while Laurie created visual interpretations based on the person’s descriptions of how they experience the world. The final exhibit included recorded audio descriptions to ensure accessibility for blind and visually impaired visitors.

“The point was to show somebody what they would see if they were looking through the eyes of one of the participants,” Billy shares. The result was a multi-sensory experience that honored both the physical and emotional dimensions of sight. “What I enjoy the most about photography is telling people’s stories or letting them tell their stories and being a conduit for them to be able to say what they want to say,” Billy shares.

One participant, Nikki, had cataracts and detached retinas. In the image created from Nikki’s description of her sight, a broad sweep of gray in varying shades dominates the frame, with a small circle in the lower-left periphery where glimpses of feet or nearby objects close to the ground are visible.

But more powerful than what Nikki physically sees is how she wants to be seen. In a description next to the photo, she shares, “I was thinking about how other people see a blind person. And I do notice how people talk to me, and often it sounds like they’re talking to a child. Or they talk a lot louder. Or I find pity in their voices. I want to say I’m still the same person. I’m a whole person.”

By photographing Nikki as she wishes to be seen based on her sacred relationship with herself — what’s unseen on the surface, what’s inside, and how she feels about herself — Billy captures the essence of who she truly is. It’s that spiritual clarity, a deeper kind of seeing, that Billy and Laurie hope others will also recognize in the images and stories they’ve helped bring into view.

When clinicians visited the exhibit, many expressed surprise and appreciation at the diversity of visual perceptions on display. Traditional medical photography had never shown them this range or depth of detail. What Billy and Laurie created wasn’t just a visual representation; it was a human connection. Laurie recalls a moment in a gift shop near the “Blind/Sight” exhibit. A mother, talking about her son, said, “I thought he was faking it [referring to his visual experiences]. I realize now he wasn’t. This helped me see.”

****

While artistic photography may not solve the material problems of illness or disability, Sacred-centered photography powerfully addresses the spiritual wounds of stigma and invisibility. Rather than capturing beautiful snapshots of life in motion, this is about seeing through the warm gaze of the human heart.

“We live in a camera culture,” Billy says, “and in that culture, photography has a privileged place. It has the power to draw people into the beauty or the misery that lies unnoticed. I try to use that power to draw people into empathy.” And what’s at the core of empathy? Love. The Sacred.

Photography that allows us to spiritually see one another is not something the photographer captures alone. It is a shared act, a collaboration between the photographer and the person being seen. It is co-created in trust, story, and mutual respect. “When I get a good picture, I never consider it like I did that,” Billy says. “It’s always we did that.”

Laurie sees the work as a spiritual exchange. “It’s not just the photographer and subject. It’s a relationship. It’s a healing exchange between the photographer and the subject and also with the people who see the work.”

“I don’t know how to exactly say it,” Billy reflects, “but I’m the one getting healed a lot of the time. I think what I do is allow people to reach out, have their say, and hopefully change others who hadn’t thought about it that way. Or hadn’t thought about it at all.”

Photography isn’t the solution to the issues of being seen, considered, and accepted. But realizing our shared desire for empathy and to be known, which can be so deeply evoked through photography, are.

What might the world look like if we focused more on heart-sight than eyesight? By looking beyond the corporeal, the tangible, and the material, can we channel our vast stores of collective empathy, our uniquely human ability to see through our hearts, to better access the Sacred living within us all?

By Suraj Arshanapally