Manoomin is Life: Preserving the Sacred Food that Grows on Water

In 900 AD, before the arrival of European settlers in America, the Anishinaabe left the East Coast, advised by one of the Seven Tribal Prophesies (known as Onwaachigewen or the Seven Fires) to seek the “food that grew on water.”

In a migration that took several centuries, the Three Fires Tribes (the Ojibwe, Ottawa, and Potawatomi) eventually settled along the Great Lakes basin. There, in shallow water, they discovered tall, slender stalks with elongated seed heads that glimmered and flashed in the early morning sun. The wild rice — Manoomin or “good berry” — and all of the plants, fish, birds, and animals that grew around the rice bed, came to be known as Manidoo Ogititgaan, or “Spirit Garden.” A healthy, thriving ecosystem that nourished all wetland life and became sacred to Indigenous customs and identity.

In our modern world, many are disconnected from understanding nature as sacred and integral to our humanity, instead seeing a compendium of resources that are available to exploit. Native American sacred ecology shines a light on ways to encourage reciprocity, and forge a movement from commodification to relationship and respect. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s decade-old, bestselling book, “Braiding Sweetgrass,” as an influential example of that sacred ecology, has blended Potowatomi wisdom with scientific knowledge to offer a pathway forward. Youth, in particular, are heeding the call.

“The Manoomin is one of the cornerstones of our tribal identity and spirituality,” says Roger LaBine, a passionate wild rice advocate and Tribal delegate of the Michigan Wild Rice Initiative. “Manoomin has been raised to the level of the four sacred medicines: tobacco, sage, sweet grass, and cedar. The cultivation of it enables us to live in balance.”

In 1972, over a millennium after Tribal migration, then 16-year-old LaBine (whose spirit name is Mitigwinaabe, pronounced mi-tig-wi-naw-bay, which means “Spirit of the Trees”) was invited by his grandmother to attend Wild Rice Camp in Northern Wisconsin. “It was one of those bumper crop years,” remembers LaBine, who is of the Sturgeon Clan of the Ojibwa Nation in the Western Upper Peninsula. “All the tribes from the surrounding area were involved. It was harmonious and social. When you start processing wild rice and trying to gather enough for one year until the following harvest, it takes a lot of people.”

In the 1970s, there were no remaining Manoomin beds in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Wild rice still grew at Tawas and Houghton Lakes, among some other beds in the Lower Peninsula. The Tribes gathered on Wisconsin’s Stella Lake for the harvesting, which took place close to Manoominikegiizis (Wild Rice Moon) in August. LaBine’s uncle and mentor, Niigaanaash (pronounced knee-gone-nosh, meaning “One Who Leads”), was committed to restoring the lost Manoomin beds.

“My uncle had a vision that he was going to try to bring Manoomin back [to the Upper Peninsula] because he remembered as a kid how much wild rice was there,” says LaBine. “In his stories to me, he said he could actually watch the rice beds recede and get smaller and smaller and disappear.”

In order to cultivate new rice beds, Nigaanaash brought burlap bags to camp to collect seed. “The last two days of harvest, we took that rice, and we started that restoration in the fall of 1972,” says LaBine. “Every year thereafter, when processing our wild rice, we would always bring rice back.”

During his first rice camp, LaBine learned the basic roles of harvesting: push-poling, knocking (ricing sticks), jigging (dancing), winnowing, cleaning, and preparing for storage. He also learned he had a gift for cultivating inter-tribal relations, especially around the campfires. “It was almost like an immersion camp for me. It has been something I’ve tried to share in all of my rice camps, that initial feeling. I observed my relatives and everyone else there, and the honor, the care, the laughter. Oh, there was laughter!” says LaBine. “All that was shared with me was priceless.”

Amid the swish of the stalks gently brushing against the sides of the canoe, the occasional splash of the “swimmers” (fish), and the trills of the “winged ones” (birds and insects) in harmony with the days-long rhythmic work, LaBine developed a deep connection with the Spirit Garden and his ancestors. “That experience was a living memory. It was around the campfires at night that the idea arose to restore the Manoomin to the way it once was.”

Passing the Torch

In 1999, Niigaanaash was diagnosed with cancer but refused treatment. “Before he walked on, Niigaanaash said I needed to fight, preserve, and protect this resource, this sacred gift from the Creator, because losing it would be very much like the loss of our language, our identity,” says LaBine.

To LaBine, accepting that vow was like “coming home.” Five decades later, LaBine, who is an enrolled member of the Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa (LVD) and a Water Resource Technician for the Tribe’s Environmental and Planning Department, continues to advocate tirelessly for the restoration and preservation of wild rice, including two decades spent in pursuit of the passage State of Michigan’s Manoomin Bill.

While it’s hard to determine how many Manoomin beds were lost over the last century, out of 198 historical sites — many of which were hundreds of acres — only six remain. One bed that was historically around 10,000 acres is now only 200. At least 139 beds exist today around the Great Lakes, including restoration sites, but nowhere near the size of the former beds.

Unfortunately, no legal protections by the State of Michigan have yet been adopted for wild rice beds, which are under threat for a variety of reasons including climate change, water pollution, invasive species, recreational boating, and oil pipelines. Recent cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency funds have also reduced or halted efforts for Manoomin preservation.

While current funding setbacks are discouraging, LaBine, who has postponed his retirement several times, maintains the vow he made to his mentor. “I have a passion for what I’m doing. I have a deep passion and a deep commitment to my ancestors who asked me to work very hard to preserve that and make Manoomin available for my grandchildren and their grandchildren. And I continue to do that work.”

Manoomin as a Keystone Species

One of the important lessons that Niigaanaash taught LaBine was that “We are in church, wherever we are.” For the Anishinaabe, there are Four Sacred Orders: the First Order are the building blocks and elements, Mother Earth, Living Water, Wind, and Fire. The Second Order are the animals — the swimmers, the winged ones, and the four-legged ones. Next is the plants, land and aquatic life of the Third Order. And finally, the Fourth Order is the Anishinaabe (or humanity), who are responsible for tending to all of the other three orders who are their relatives.

“We need to live in balance. We are not above any one of those orders. Those all have a spirit. They are our brother or sister. You do not do anything to them that you would not do to your sisters, brothers, aunties, or uncles,” says LaBine. “Niigaanaash directed me to say, even when you go out to Gititigaan, you have to announce yourself. It’s a sacred gift. You have to do it for any other orders that sacrifice for you. And you only take what you need.”

Wild Rice is a keystone species, which means that other species in its ecosystem largely depend upon it. Its vitality indicates healthy water, healthy plants, and healthy creatures. A healthy, sustainable wild rice bed provides a grain that is nutritionally superior to cultivated rice, with over 50 percent more of all nutrients.

Preservation of Manoomin and its habitats, LaBine and others believe, not only fulfills Tribal prophesies and preserves Tribal culture, but has ramifications and importance for all. The Anishinaabe consider themselves the knowledge-keepers of the sacred relationship to all living things. According to Tribal prophecy, they will one day be asked to share it with the rest of humanity to work in cooperation to preserve our precious earth before it’s too late.

“In our teachings, we are told about what we call the Seventh and Eighth Fires. At the lighting of the Eighth Fire, we are being warned we are going to come to a time where we have to make a decision about which way we want to proceed,” says LaBine. “The upper road is to technology. And that road is going to lead us to destruction. The lower road goes back to the traditional ways of thinking.”

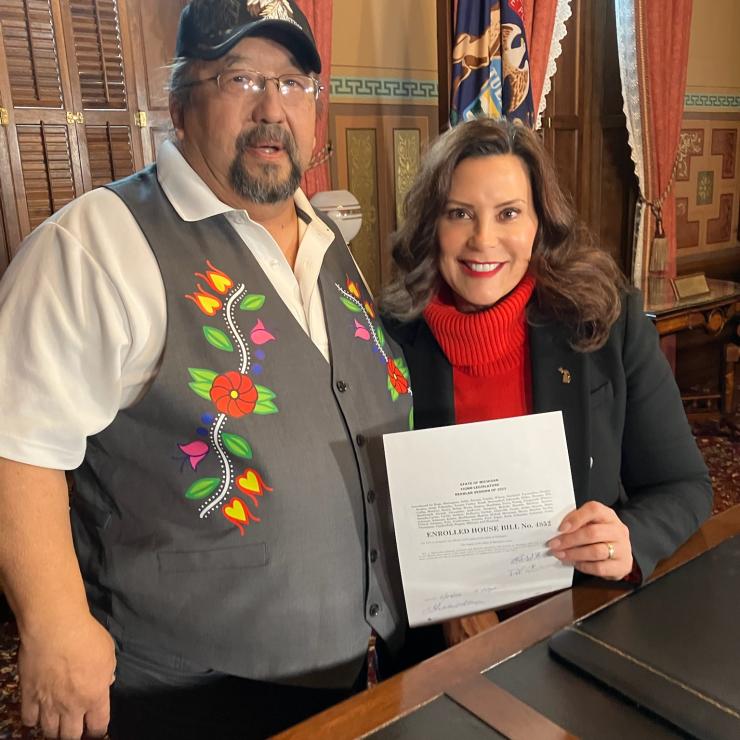

In 2023, LaBine and those who worked alongside him celebrated the fruit of their hard work when Michigan’s Governor Gretchen Whitmer proclaimed Manoomin as the State Native Grain, the first state in the nation to do so. This designation, in addition to the work of Michigan’s Wild Rice Initiative, has kept LaBine busy with talks around the country, rice camps, fundraising, restoration, and preservation.

So much is still left to be done, especially in light of recent federal and state funding cuts. But the legacy of Manoomin asks us all to consider our own sacred relationship to the earth and its gifts and inhabitants.

“At one time, (all of us) were able to communicate with those spirits and all those other orders,” says LaBine. “But now we no longer have that ability. We at the Fourth Order have that right and responsibility to speak for the other orders, for their perfection. We have to live in balance. We’re advocating and asking for you to recognize that these resources need to be protected and healed if we are going to survive.”

And who does LaBine mean by “we”? All of us who call Earth our home.

To learn more about Manoomin and Michigan’s Wild Rice Initiative, a comprehensive Manoomin Stewardship Guide is available online. The Anishinaabe welcome the volunteer participation of non-tribal members in Wild Rice Camps.

By Theresa Coty O’Neil