Love in a Sacred City: How One Priest Builds Peace Through Theater and Interfaith Dialogue

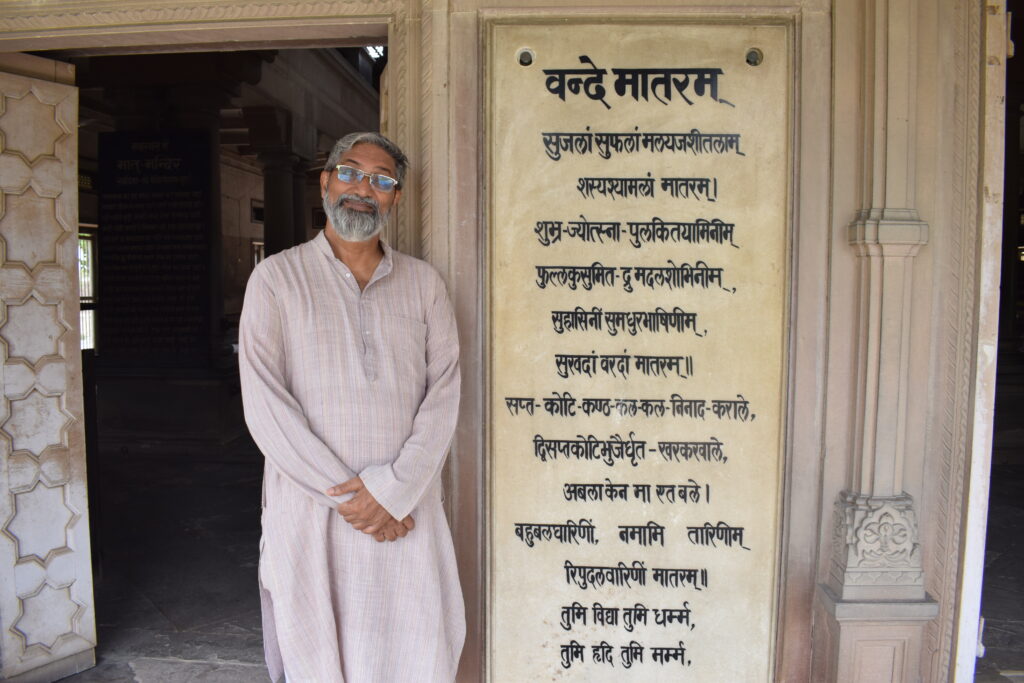

In the sweltering May heat under the shade of a lush mango tree, 66-year-old Catholic priest Rev. Anand Mathew’s voice rang clear.

“We need to preserve Varanasi’s pluralism,” said Mathew, wearing a homespun cotton tunic and a stole around his neck. The low caste village leatherworkers crowded around him for a peace meeting on the outskirts of Varanasi, a sacred city on the banks of the River Ganges.

“We won’t let communal forces break our religious tolerance,” Mathew went on, as more villagers sat around him on straw mats under the tree. For the Catholic priest who’s been campaigning for justice within the church and outside in this sacred city for more than three decades, these peace-focused meet-ups have helped him bring together segregated communities.

In Varanasi’s Maheshpur village, dotted with fields of wheat and rice, thatched huts and cow sheds, the decision to hold a meeting wasn’t arbitrary for Mathew.

Poverty — most visible on people’s bodies and homes here — is a stark contrast to Varanasi’s newly refurbished eighteenth-century Kashi Vishwanath Temple by the Modi government to glamorize the city and rake in revenue. Yet in Maheshpur, residents have faced social exclusion and discrimination for decades, including limited access to water, electricity, education and burial grounds. This new development has personified these divisions.

But the wound runs deeper than infrastructure inequality or exclusion. Varanasi, long a symbol of shared, multifaith belonging, is now seeing its spiritual essence threatened.

“That’s why we want to build peace in tense Hindu-Muslim and caste-conscious settlements,” says Arvind Kumar, a local activist who works closely with Mathew. “In the last three months we’ve done at least two peace meetings every week.”

Over the last decade, claims by Hindu nationalists that the seventeenth century Gyanvapi Mosque was built on the grounds of the original Vishwanath Temple, which dates back thousands of years, have heightened communal tension in local villages. Hindu vigilante groups combing alleyways, mosques and Muslim homes to find Hindu idols and evidence of temples have caused community ties to fray further.

Though they’ve historically coexisted, Varanasi’s Hindu and Muslim communities in both cities and villages are now experiencing increased polarization, fueled by disputes over religious sites and claims about the past. “This is an alarming trend,” said Mathew, who sets off on his motorized scooter every week to lead peace meetings in underserved villages and urban slums.

On finding an empty spot in a village square or squatter settlement, he adorns it with a “peace banner” and then gets women and men from marginalized communities to talk about their domestic and socio-economic problems to break the ice.

In the millennia-old city, Hindus and Muslims have had a long tradition of shared religious spaces, including Sufi shrines and mosques. The conversations get livelier as villagers join in the sensory experience of the city’s atmosphere — the old alleyways, riverfront and royal palaces, and multifaith history marked by both harmony and violence.

“Whenever we think of communal harmony-building, Father Anand’s name comes up,” says Muniza Khan, a researcher and social activist based in Varanasi. “He’s not just a priest but a mobilizer who’s ready to help all victims of violence.”

Khan remembers how the Catholic priest stood firmly by the side of a 17-year-old Muslim shop attendant who was brutally beaten up and branded a “terrorist” by Hindu vigilantes last April when he was walking by the river one evening.

“As a faith leader, I’m reminding people to counter hate with love and stand together as Varanasi always has,” Mathew shared with University of Southern California’s Center for Religion and Civic Culture.

The desire to help the marginalized incepted quite early in Mathew’s life.

Raised in a traditional Syrian Catholic family in South India, deprivation marked his early childhood, although his education was never compromised. His father, a local bus attendant, and his mother, a modest farmer who supplemented their family income by selling milk and poultry, always pushed Mathew and his eight siblings to prioritize learning.

While devotional prayers at home and catechism classes at school grounded Mathew in the Christian way of life, the desire to become a missionary in North India, so different from his village in the country’s south, came a little later.

“A priest was visiting our village school and he asked us who wants to join the missionaries,” Mathew recalls. “I felt drawn to the idea of becoming a priest.” Doing so would allow him to engage with the work he found most sacred: cultivating peace through divine acceptance. Through seeing one another wholly and without judgement. Through love.

Mathew’s recently formed Souhard Peace Center — from the Hindi word Souhard, meaning harmony and solidarity, but also an acronym for Solidarity, Oneness, Humanism, Amity, Reconciliation and Diversity — not only prioritizes peace in the villages but also in the urban slums, shantytowns, and deprived colonies.

In Varanasi’s local schools, the priest also offers classes on peace, constitutional values and India’s composite culture to counter religious fundamentalism. In 1975, Mathew moved to Varanasi, four years after joining Indian Missionary Society — a Catholic religious congregation prioritizing community building and development of marginalized communities, especially women and children.

India’s former prime minister had declared an emergency across the country involving wide-scale suspension of civil liberties and arrests of political opponents. In villages, forced sterilization campaigns had not only intensified fear and lack of trust in the government, but also disrupted rural communities. “It was shocking to witness its effects in Varanasi’s villages,” recalls Mathew. “I also saw the blatant displays of caste discrimination and patriarchy.”

Yet, the generosity and warmth of villagers created more questions in his mind, including how he could touch the lives of ordinary people through spiritual work. Taking the Sacred as his compass — seeing every human as divine — Mathew began cycling to villages to pass on Gospel messages for joyful living while also deepening his social involvements.

Theater, a medium of communication that had been his passion since childhood, seemed like an area Mathew could develop further to spread peace and harmony. “Another Catholic priest and I set up a theater group in the city, and we slowly turned it into a regular repertoire,” Mathew says, in reference to being appointed as the director of Vishwa Jyoti Communications, a media center committed to communal harmony and socio-cultural development, back in 1994.

Through street theater, dance, songs and improvisational theater, the Catholic priest began to build bridges between communities, challenging stereotypes and promoting cross-cultural dialogue in ways the villages hadn’t been exposed to.

“Father Anand has been able to venture into people’s hearts,” says Rev. Praveen Joshi, the director of Vishwa Jyoti Communications. “Even though there have been threats from the local administration, his plays have won people over.”

Staged 10,600 times across Indian villages and cities, the 126 plays directed and produced by Mathew stirred people’s hearts and unmasked new ideas. Over the years, he even began to form theater troupes across India, and ventured into Madagascar, Nepal and Sri Lanka to conduct training and form troupes.

But the priest wasn’t just keen on breaking the social barriers by exploring themes like identity, belonging and difference. He wanted to spark inter-faith dialogue through theater and grow a community of peace advocates. Though rooted in Christianity, Mathew’s immersion in other spiritual traditions, including Gandhian non-violence and civil resistance, and in the spirituality of Indian ashrams and ecological movements, helped him broaden his reach.

“We’ve been staging plays, hosting inter-faith meets, and sensitizing people about Gandhi’s and Kabir’s ideas for years,” said Vivek Das, a priest at Kabir Chaura Matha, an ashram dedicated to the teachings of fifteenth century mystic poet-saint Kabir.

From ashrams like Kabir’s, Das says, they’ve been organizing several peace marches winding down the city’s intricate network of narrow, winding alleyways and riverine steps along the River Ganges, culminating in sacred sites for rituals, bathing and cremation.

Their work is rooted in the belief that peace is not the absence of violence — it is the active, daily practice of love. “Religion without compassion not only limits you as a person, but also the communities you serve,” Mathew once said. He has also urged “people to replace hatred with ‘xenophilia’ — love for strangers and enemies.”

When religious polarization gets hotter during election season or outbreaks of communal violence occur, Mathew and his collaborators gather in groups, sensitize, and cool tempers. “We organized peace rallies and prayer meets when the Gandhian social service organization, the Sarva Seva Sangh, was demolished two years ago,” says Jagriti Rahi, a Gandhian activist.

Gandhi’s ideology, especially the emphasis on non-violence and self-reliance, are especially threatened in Varanasi due to the focus on rapid economic development and consumerism. On their marches, the peace advocates often mobilize the city’s marginalized weavers, domestic workers and slum dwellers who have been adversely affected by Varanasi’s redevelopment, hailed by the government as a symbol of spiritual revival.

“We’ve gained nothing from this redevelopment,” said a shopkeeper living in the city’s old quarters. “But peace activists like Father Anand have helped us fight hate through love and tolerance-centered reforms.”

Love and joyful living, words that Mathew uses often, reflect not only in his peace work in the city but also in the way he names and plans his campaigns. Over the last three years, despite religious extremists pasting posters along the banks of the river, the priest has been spearheading poetic symposiums and inter-faith meets like Paigam-e-Mohabbat (message of love) at communally-sensitive places to bring into focus Varanasi’s composite culture.

A few years ago, inspired by Pope Francis’s encyclical Laudato si’, he initiated Laudato si’ in-action — a campaign phrase he coined to get more faith leaders and civil society actors involved in caring for the environment.

Also deeply invested in nature, Mathew led them into creating self-sustaining and rapidly growing forests in urban and other degraded areas through the Japanese Miyawaki method mimicking natural forest ecosystems.

“[Father] Anand brings the cultural element to protests,” says Neeti Bhai, Mathew’s friend and mentor. “Even though theater has been his primary pursuit, he also uses other cultural mediums to dispel hate and bring diverse people together.”

Spiritual humanism — the conviction that every human holds divine worth and that loving acceptance is the path to justice — rather than cultic priesthood, is what keeps Mathew rooted.

Even though the Catholic priest offers reflections, prays over the sick, conducts religious retreats and works closely with pastors of all Christian denominations, his spirituality has always led him to collaborate with anyone on behalf of those living in poverty. Even government crackdowns, surveillance and arrests have not deterred him.

“Every time I’m arrested, I feel happy because so many innocents are languishing in jail without trial,” he smiles. “Religion often speaks of life after death, but I want to be there for the most marginalized in this life itself.”

Mathew’s work reminds us: What if true coexistence requires that we see the Sacred in each other — even across differences, perhaps especially in conflict?

By Priyadarshini Sen