Former Child Soldier Turned Philanthropist: Ishmeal Alfred Charles and the Sick Pikin Project

Content Warning: This article contains descriptions of violence, exploitation, and the experiences of child soldiers. Reader discretion is advised.

Emerging from the battlefield in 1994, Ishmeal Alfred Charles’ whole body sank under the weight of exhaustion. His tattered clothes, grimaced face, and haggard gait were harrowing evidence of the three long years he spent as a child soldier.

He was just eight years old when a civil war broke out in his country, Sierra Leone, in 1991. The following year, rebels under the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) abducted him after overpowering government troops in Kono, a district east of the African country, where he lived with his father.

Seeking to control the country’s natural resources and displace a political class it considered corrupt and wasteful, the RUF abducted children as fighters, mutilating or decapitating those who resisted. Three times, Charles had come very close to death. As he finally emerged from the jungle, gratitude filled his heart.

“On one occasion, the second rebel group that captured me after I escaped from the first lined us up and asked, ‘Do you want long sleeves or short sleeves?’ They were killing and cutting off arms, but when they got distracted by an Alpha Jet, I escaped,” Charles recalls.

This sense of gratitude would soon push him to use weekly fasting and daily prayers in an attempt to “hear from God” and receive “His directions” toward fulfilling what he felt was the divine purpose for his preservation in a war that claimed between 50,000 and 200,000 lives.

The answer came 24 years after his escape from the jungle and 16 years after the 11-year civil war ended in 2002. A rare experience with a critically sick child projected Charles to become a lifeline for hundreds of children with emergency medical conditions in Sierra Leone, providing access to life-saving medical surgeries that are often unavailable or too expensive in the country.

Rich in Mineral Wealth, Poor in Public Health

Sitting on a 71,740-square-kilometer area by the Atlantic coast of West Africa, Sierra Leone has abundant natural resources, including gold, diamonds, iron ore, coltan and platinum. Despite this geological wealth, the country of 8.5 million people has one of the weakest healthcare systems in Africa.

The country has suffered years of economic mismanagement, corruption, political instability, a steadily rising external debt, weak public revenue, and over-reliance on raw mineral exports. The result? The world’s fourth poorest economy by GDP.

These governance and economic fatigues have meant minimal investment in healthcare. Annually, the sector has received just between 5% and 7% of the national budget over the last decade — a far cry from the 15% African leaders agreed on in 2001.

The result is evident in many ways, including in the country’s high child mortality rate at 94.3 per 1000 live births, which is nearly twice the global average. As hyperinflation (56% in 2023) pushes the poverty rate to 32.7%, access to quality healthcare remains a luxury for most citizens.

By 2018, Charles was several years into his role as programs manager for Caritas, the Roman Catholic charity, in the country’s capital, Freetown. One morning that year, a desperate mother rushed into the charity’s office with her critically sick baby seeking help. Mustapha, the baby, had biliary atresia, a life-threatening condition in which the bile ducts (tubes) carrying digestion-enabling fluids from the liver to the small intestines are blocked.

His life depended on an urgent liver transplant, but no hospital in Sierra Leone could operate him. His mother also could not afford the $36,000 required for the operation in India.

Sadly, Caritas had no resources at the time to help. But witnessing the baby’s critical condition and his mother’s devastation, Charles was spurred to action.

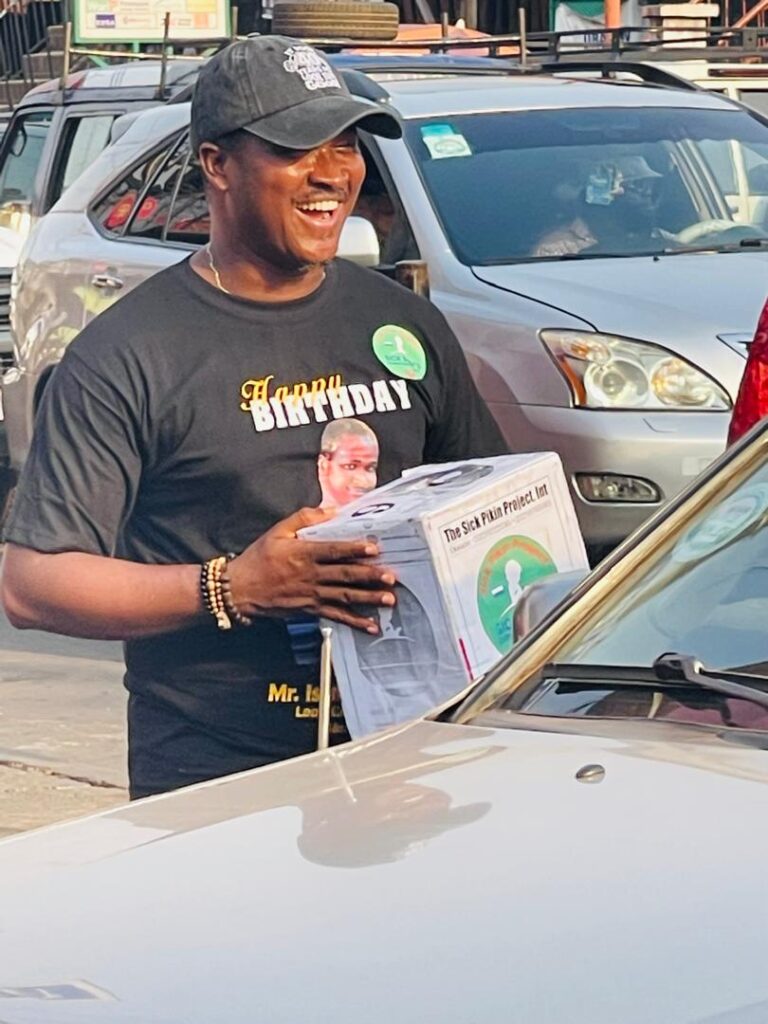

He took photos with Mustapha and posted them to social media, calling for donations. He also created donation boxes, printed Mustapha’s photos on them, and mobilized volunteers who stood at strategic places across Freetown’s streets soliciting donations from passersby.

“It started going viral, and a couple of journalists picked it up,” Charles recalls. Within months, he had raised the money. Mustapha’s life was saved from a successful surgery in India.

But that was just the beginning.

As more parents with sick children heard through the national news and word of mouth how Mustapha received help, they came to Charles at the Caritas office asking that he do the same for their children.

At this point, Charles says, “I realized this was the reason God preserved me in the jungle — to give back and help these dying children,” a tear falling from his right eye. started the campaign all over again, raising funds for one child at a time. He called it the Sick Pikin Project, which translates to the Sick Child Project.

“Sick Pikin has given me back my joy,” says Mabinty Kargbo, a mother of two in her 30s, with a grin. Mabinty trades in seasoning cubes and onions to earn $16 monthly and in 2023, her six-year-old son, John, was dying from a congenital heart disease. When a pediatric cardiologist told her that John’s condition required an open heart surgery outside the country, she cried to the Sick Pikin Project in despair.

“With a $12,500 donation from a former Sierra Leonean footballer and funds from other sources, we flew John to India,” says Alice Morsho Bah, the coordinator of the Project, which is now registered in the US and the UK to allow tax-deductible donations from those countries.

The project has now helped 309 children, including 247 operated on in India. Every time Charles takes up a case, “My wife and I would pray, and when we want to make any critical decision, we fast and invite God to take the lead. We reflect on the fact that this is what God wants me to do,” he says.

Charles’ experience and dedication suggests that what is most broken in our world is not only our systems, but our capacity to remember that every life is holy and worth defending. The real healing begins when a community chooses to see every child as sacred, worthy of love and protection.

Love Without Boundaries

On Good Friday in 2025, an emotional scene played out on a street in Freetown. A homeless and unsheltered woman with acute mental illness met five-year-old Malaika dancing and decided to join him. The boy, holding a donation box, was performing for passersby to raise funds. The scene attracted a small crowd, which donated more money as the dance battle raged on.

Minutes into the dance, Malaika ran to his father and asked him to buy water for the old woman. His father handed him six leones (less than ten cents) to give to the woman. She collected the coins but threw 4 leones back into Malaika’s box. Her gesture got Malaika emotionally charged; he ran and hugged her lovingly, not caring that she had probably not bathed in weeks or months.

Malaika is Charles’s biological son, but his display of empathy and nondiscrimination sprang from what he and other children have learned from the former child soldier — that love heals, love begets love, and everyone deserves it.

At the Project’s yearly ticketed charity concerts for children, Charles teaches the children to give back when they get the chance because “the principle of compassion is central to Christian teachings, which call on us to serve others selflessly and tackle Sierra Leone’s challenges,” he says. “Love knows no boundaries and transcends gender, religion, and mental status, uniting us in our shared humanity.”

Still, the now 42-year-old Charles, who documented the journey of his transformation from child soldier to humanitarian in his book, is sometimes weighed down by unmet needs.

“As I speak, 36 children are on the list for aid. With so many kids needing help, the mental pressure on me becomes too much,” he confesses. “Our volunteers always hear that we are going to pay like $15,000 or more for a child. That is over LE 300 million, and they don’t get half a million for all the work they do. Few understand and are very consistent, but we have too much turnover.”

But what Charles does not know is that his staying power and observed commitment to the sacred and relentless, resilient power of love, especially amid what can feel like insurmountable challenges, are the reasons some volunteers and workers have stayed loyal to Charles and their mission despite low compensation.

“His influence has allowed me to see the world as a community, where my actions affect others,” says Bar, the project’s coordinator. “It makes me understand that we should not be selfish: if you don’t have the finances, give your time.”

Charles says encouragement from his close community and self-reassurance that their work is vitally filling a social gap and fulfilling a divine purpose make him a no-quitter.

“I have had a lot of pain, hunger, and poverty. Everything that I do today is pre-informed and predesigned by those experiences that I have had. It’s my foundational reality. So when a child is sick, I understand what that means,” he says.

Charles’ story reminds us that what transforms broken systems is not only money or medicine, but a way of seeing each life as sacred and each person as kin. When we root solutions in love and collective responsibility, healing extends beyond the direct recipient — it ripples through families, volunteers and whole communities. His work shows that the Sacred is not a miracle reserved for the few, but a daily practice available to all of us: to act with compassion, to bear one another’s burdens, and to believe that shared flourishing begins with shared care.

By Innocent Eteng

Return to the Spiritual Solutions Library.