Casa La Serena and the Sacred Heart of Activism

Content Warning: This article contains content that some readers may find distressing, including references to violence, exploitation, trauma, and other sensitive subject matter. Please take care while reading.

For the women entering its doors, Casa La Serena can be like coming upon an oasis after being lost in the desert. The house garden is lush despite the dry season lingering in Oaxaca City, Mexico. The birdsong is louder than the cars passing nearby.

That’s what the female human rights and environmental activists are seeking when they arrive at Casa La Serena as they face their own physical and mental health crises. Many of these crises are tied to generational traumas from a region that has struggled to make meaningful gains in resolving the challenges these women search solutions to.

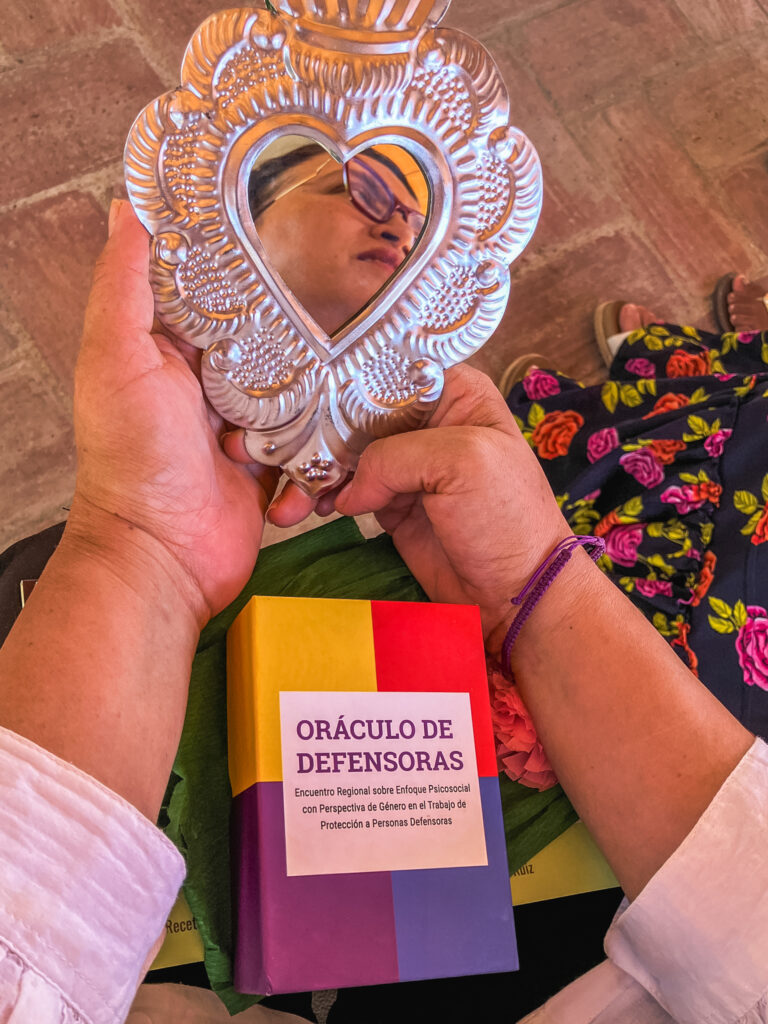

The walls that protect the house are colorful, with paintings done by participants in the retreat program that takes place within. These are all signs that the house is well cared for — life is flourishing here. Peace is found here. Women appear at the center of hope-filled murals, surrounded by nature, community and powerful symbols of ancestral roots.

Right next to the mural created by defenders from El Salvador is a square space with short grass. “This mural is an altar for me,” says Nallely Guadalupe Tello Méndez, a director at Casa la Serena. “We always start the retreats here with a ritual to ask for permission, turning to all four cardinal directions, to all the energies, with the intention that the work we do serves the colleagues who come to stay here,” says Tello Méndez. She points to a tree between the ritual space and the gate. “We believe this tree has spirits. It is a guardian of this space.”

Casa La Serena is managed by Consorcio Oaxaca, an Oaxacan nonprofit. They organize capacity-building events for women, advocate for the elimination of gender-based violence in Mexico and have worked with girls and women in rural areas of Oaxaca, among other initiatives. Consorcio Oaxaca is part of a network of some 300 organizations throughout Central America, Mesoamerican Initiative of Women Human Rights Defenders (IM-Defensoras), who are united by the common goal of achieving justice for women throughout the region. The network runs two retreat houses: Casa La Serena in Oaxaca and Casa La Siguata in Honduras.

“This is a retreat that primarily addresses situations of exhaustion, fatigue, and burnout,” says Tello Méndez. The retreats are usually attended by human rights and environmental activists from the network. Sometimes attendees from other countries join the group, just like Claudia Mayerli Campo Cisneros did in April 2025. The 33-year-old Bogotá-based human rights activist works with the Colombian organization Minga, in regions controlled by military groups.

Campo Cisneros came to Casa La Serena because she was suffering from depression. “It is very difficult to listen to the stories of previous generations who have gone through the same struggles that we are experiencing,” she said. “It creates a lot of hopelessness and exhaustion. I feel like what I do is not changing anything.”

Another activist, Felicitas Martínez Solano, from the state of Guerrero in Mexico, is an advocate for better women’s reproductive health and the rights of traditional midwives. “The biggest challenge is that even if the laws are there, they are not implemented by the institutions,” says Martínez Solano. She came to Casa La Serena because of psoriasis, an autoimmune disease that can be caused by stress and unhealthy eating habits, among other factors. Martínez Solano says for her, it may have been both.

Hopelessness is a common feeling and a heavy burden among activists. It’s frequently not merely a psychological fatigue, but also an ailment of the soul — a deep spiritual dissonance born from witnessing sustained injustices.

Living Under Threat

Latin America is considered the most dangerous region for activists with more than 126 activists killed here in 2023. Local human rights and environmental defenders face death threats, physical attacks, disappearances and attempted killings. According to Global Witness, an organization that collects data on murders of environmental activists, 196 were killed in 2023 globally. Latin America again had the highest numbers of recorded killings in the world. Most of them occurred in Colombia.

“There is uncertainty about security, and a constant threat to life precisely because of the violent context,” says Campo Cisneros. For work, she frequents regions where, as she says, a shooting could happen at any time. “We know we are in danger. All we do is trust. Our work would not be possible without it.”

That is where sacred trust comes into play. The need for there to be a spiritual force at their backs, and the faithful understanding that allows these activists to continue their critical, missional work in harsh conditions.

The IM-Defensoras also keeps a record of attacks against activists from the network. They have documented 35,077 attacks against 8,926 women defenders between 2012 and 2023. Compounding the fear and reality of violent attacks, activists who are also mothers face additional social pressures and lack of balance between work, home life and care for themselves.

Casa La Serena provides the physical space, the gift of time, and the safe, spiritual environment that allows these activists to breathe, buffered from the challenges and traumas that pockmark their daily lives. Here, the champions of the oppressed, advocates of the silent are given the opportunity not only to decompress, but to be cared for, and to open themselves, even to mourn. There are risks in doing that, too – the risks that come with looking inside. Trauma-grieving can run like a waterfall when the body, mind and spirit finally feel safe.

Rituals and Collective Healing

Casa La Serena has hosted around 400 defenders since 2016, addressing five dimensions of their being: physical, mental, psychological, energetic and spiritual. From a healthy and particular diet — no coffee or meat is allowed inside — to practicing martial arts, therapies of all kinds and indigenous rituals, participants have a chance to reboot their bodies and minds in ten days. The program is always unique, tailored to the needs of each individual and each group.

From the beginning, this experience has been rooted in the Sacred. While there are defenders who say they do not believe in anything, Tello Méndez considers all participants of the program spiritual. “I believe that the colleagues who come here live and defend their spirituality all the time. For example, when they defend the river, they are not only defending the water, but they are also defending the spirit of the water. The spirit that was with their great-great-grandparents, their grandparents, their parents,” she says.

The spiritual practices at Casa La Serena, such as rituals and traditional medicine, are all rooted in indigenous beliefs and ancestral knowledge. “It is part of this place. In Oaxaca, we all grew up with it,” Tello Méndez explains.

The team always invites the activists to the ritual of the Zapotec temazcal, which takes place inside an adobe structure. “We enter, we greet everyone, we do breathing exercises and then we ask permission from the guardians of the place,” says Norma Jaquelina Yescas Contreras. A traditional healer, or curandera, she leads the Zapotec ritual for Casa La Serena. It is similar to a sweat lodge, but temazcal works on several levels. “It is a ritual to detoxify the body and work with the emotions,” says Yescas Contreras.

As they enter the temazcal, she asks participants to set an intention for the ritual. “Everyone brings their traumas. I help them with this energy, but they also have to do their own work,” the healer says. She works with plants inside the temazcal, using rosemary, basil and rue to cleanse the women before and during the ritual. If necessary, she also does traditional energy cleansing outside of the temazcal ritual.

For indigenous healers in Oaxaca, the use of plants is a way to connect with Mother Earth. Finding the lost connection is the purpose of the temazcal ritual. “We ask the four elements to help us during the ceremony. That’s when I begin chanting,” says Yescas Contreras and starts singing one of the chants she uses inside the temazcal to call the elements in.

Tierra es mi cuerpo, agua es mi sangre, aire es mi aliento y fuego mi espíritu.

(The Earth is my body, water is my blood, air is my breath and fire is my spirit.)

“Being in the temazcal is like going back to the mother’s womb — it is where we felt the connection,” says the healer. This Sacred connection, unlike almost any other experience, is shared by every human being.

While the temazcal that the activists attend is a Zapotec ritual, Latin American defenders are often familiar with similar practices. “I think we all have altars in our homes, even if they are Catholic,” says Felicitas Martínez Solano. “And as indigenous people, we have our spirituality, our rituals, that we must pass on to the next generations.”

María Dolores Hernandez Gil, a journalist and nonprofit collaborator from Sonora state in northern Mexico, agrees. “I am from a region with a [big] native population,” she says. “Even though there is no temazcal, the spirituality is present, for example in the form of traditional medicine.”

Casa La Serena has also welcomed colleagues from other countries in Africa, Europe and the Middle East who have come to seek inspiration. “Some of them are still looking for ways to reconnect,” says Tello Méndez of her observations of how spirituality is addressed in other continents.

Spiritual Care in Daily Life

At the end of the retreat, women make a list of their personal strategies to help care for the self and the spirit that they hope to incorporate into their daily lives. Hernandez Gil wants to exercise more, make plans with her daughters and work more with herbs. “Plants are already part of my daily life, but now I want to share them with more people,” she says. Martínez Solano also plans to spend more time with her daughters.

Claudia Campo Cisneros plans to continue meditation and other spiritual practices. “One of my spiritual needs is to reconnect with my ancestors. I want to be able to continue our healing rituals, which are very holistic,” she says. “Without the spiritual component, it would be very difficult to find ourselves, to forgive ourselves, to know ourselves. And to heal many of the wounds we have, especially those related to family trauma,” says the Colombian activist.

Casa La Serena’s work isn’t without challenges, such as demand outpacing what they can provide. Another is that there is a lack of spiritual self-care practices within the organizations themselves. While many position themselves against capitalism and patriarchy, activist organizations sometimes adopt the strategies and mindsets of these systems that are difficult to disrupt, such as work overload.

Overcoming these challenges is part of their sacred collective. “We strongly believe in collective action. We say networks save. It is the women themselves, the defenders themselves, who are helping other defenders,” Tello Méndez concludes.

At the same time, for the IM-Defensoras, sacred self-care is at the heart of activism. Spiritual care, collective care, and healing are fundamental political strategies that drive resistance. “When we talk about caring, we are talking about caring for life. The life of each colleague and the life of our movements,” Tello Méndez explains. “Taking care of defenders is part of a broader strategy of holistic feminist protection.”

Casa La Serena and this network of fierce women activists draw upon spiritual wisdom like a depthless, never-ending well. Contrary to the human body and psyche, this sacred well never tires or loses hope.

While secular approaches to “healing the healers” may offer practical tools and temporary relief, resources rooted in the Sacred reach deeper existential despair. Spiritual care, stemming from love and hope as strong as steel, nourishes the soul in ways that ignite resilience and the power to endure.

Return to the Spiritual Solutions Library.